A Tale of Two Memes: The Powerful Connection Between Trayvon Martin and Chen Guangcheng

On the surface, the stories of a young man killed in Florida and a blind Chinese activist couldn't be more different. And yet.

From the outset, the stories of Trayvon Martin and Chen Guangcheng couldn't have seemed more different. One, a young black man shot to death in central Florida while carrying a bag of Skittles. The other, a blind lawyer activist in rural Shandong held under illegal detention in his own home.

But in recent months, both men became sensations on their respective Internets, which are largely divided by linguistic and technical barriers. In the United States this past March, it was impossible to ignore the name of Trayvon Martin, or forget the hoodie he was wearing. And in China this past year, although Chen Guangcheng's name was officially censored from search queries, his name and face were on the fingertips of web activists as they found ways to advocate for his release. In both cases, sustained internet activity kept the conversations about these two men in public discourse.

The Internet hubbub wasn't simply thousands of people clicking or Facebook-liking, though those actions were certainly involved. Rather, activists of the internet generation deployed the creativity of memes. Yes, those memes. Usually associated with LOLCats and dancing babies, memes go viral swiftly and encourage user participation. People mix and remix them along the way, helping them morph and adapt like biological viruses.

Trayvon Martin's story, though well-known now, didn't immediately claim attention and in fact received scant coverage in news media shortly after his death. That began to change with the help of social media. Seeing a note on a Howard University mailing list, a concerned outsider started a Change.org petition demanding an investigation. It would become the largest petition in the web site's history.

The petition initially had a slow start. A few days later, Daniel Maree, a digital strategist based in New York, issued a YouTube video calling for people to wear hoodies in support of Trayvon Martin's case. Dubbing it the Million Hoodie March, he sparked a nationwide meme. Social-media feeds soon filled with supporters of all races and backgrounds donning hoodies on their profile pictures and photo posts. The once apolitical act of slipping on a hoodie transformed into a powerful collective statement of solidarity with the Martin family.

"With this idea of anonymity and the inability to verify, a signature doesn't mean as much online," Kenyatta Cheese noted to me. Cheese co-founded Know Your Meme, a popular meme archival and research site, and he contributed research on the hoodie meme. He told me that the act of signing petitions is an excellent way to show mass in physical public space. Different techniques, like image memes, are often more effective for getting attention online.

"What does mean as much online," he continued, "are the reblogs, the retweets, the likes, the favorites. When you're in a social environment, the more that you can create content that lends itself toward that sort of endorsement, the faster it spreads."

What helped was that the meme spread not just amongst average social media users but also with what he called "supernodes," i.e., celebrities, who magnified the meme when they themselves put on hoodies. And per Maree's original call to action, the meme leapt into the offline world when citizens around the nation led hoodie marches and posted pictures. Weeks later, Martin's alleged murderer was arrested.

"I kind of just began from a personal anecdote of walking down the streets of New York and sometimes feeling that I'm being judged as suspicious for wearing a hoodie," explained Maree in a phone interview. "The idea of transforming that image of a young African American man in a hoodie as a symbol of unity and focusing on other than what it's judged as -- I thought that felt pretty powerful."

Certainly, memes do not a movement make. Maree credits the early responders who helped magnify his initial call to action, and the hoodie meme became part of a larger push that included the Occupy movement, celebrities, broadcast media, Change.org, and physical-world protests, among others. But the meme charged the movement with personal urgency and added symbolism and visual power to the discussions.

Remarkably, just a few months prior, China's internet had experienced a similar explosion of activity. In November 2011, net activists began posting photos of themselves wearing sunglasses on Sina Weibo, China's most popular Twitter-like microblog service. It started as a trickle but soon grew into dozens and dozens of photos and comics. Wearing sunglasses, like wearing a hoodie, is by itself apolitical. The power lay in the collective action, distributed across a network of supporters.

Netizens were posting photos of themselves as part of a project called Dark Glasses.Portrait, kicked off by an anonymous comic and social-media artist named Crazy Crab. Inspired by JR's Inside Out Project, he called for a simple action: wear sunglasses or blindfolds in support of the blind activist lawyer Chen Guangcheng.

Crazy Crab began collecting and organizing photos and responses on his web site. He told me they first streamed in from mainland China and Hong Kong, and within a week he was collecting foreigners' submissions. After his site was blocked in China, users simply posted the images directly onto Sina Weibo, where they slipped past keyword search algorithms and human censors. How could a censor differentiate between a sunglasses photo in support of Chen Guangcheng, or a self portrait on a sunny day?

And it wasn't limited to online action. As the meme's popularity grew, users printed out posters and t-shirts consisting of a mosaic of supporters made to look like Chen's face. His distinctive face was placed onto "Free CGC" car stickers made to look like "Free KFC" ads, and netizens regularly posted pictures of him, either by himself or juxtaposed alongside imagery like the Statue of Liberty and the Berlin Wall. A small group organized a sunglass-wearing flash mob in Linyi, a town close to where Chen was being held.

In China, where online speech and public assembly are highly limited, the role of internet memes is quite clear. Posting frequent demands to release Chen Guangcheng could get your posts, if not your entire account, deleted. But posting images of yourself and your friends in sunglasses looks innocuous to the uninformed.

Internet authorities, of course, are not oblivious to this power, and once they catch on to a growing meme, they often block it. But as quickly as one word or image is blocked, a new, remixed version springs up. After Chen Guangcheng's dramatic escape from illegal detention, censors shifted into high gear. Words such as "blind man", "sunglasses" and even the name of A Bing, a popular blind musician, were blocked from searches as netizens rapidly tried to disseminate and discuss the news within the Chinese web. Even then, messages slipped out in the form of veiled references to Shawshank Redemption. The relentlessness of meme culture found cracks in the relentlessness of China's censorship regime.

"This platform [the internet] is equal," Crazy Crab explained in an email interview in Mandarin. "With this platform, I don't need to go through the newspaper and magazines and other kinds of traditional media to send out my own voice. If I have a good idea, I can become the media." This is a powerful notion in a country where official media must answer to government propaganda officials.

It's more difficult to sort out the role of internet memes in the US, where opportunities for public expression are diverse. In an environment with the legal right to public speech and assembly, memes seem comically ineffectual. How could an image posted to Tumblr or Facebook possibly be helpful when there are so many other proven channels to try?

"There were a number of images that went viral with bad information," noted Cheese. "These mostly fake images of Trayvon were posted on Facebook with false information about him and his background, trying to paint him as this unsympathetic character." The meme provided a countervailing and, soon, overwhelming alternative picture of the young man.

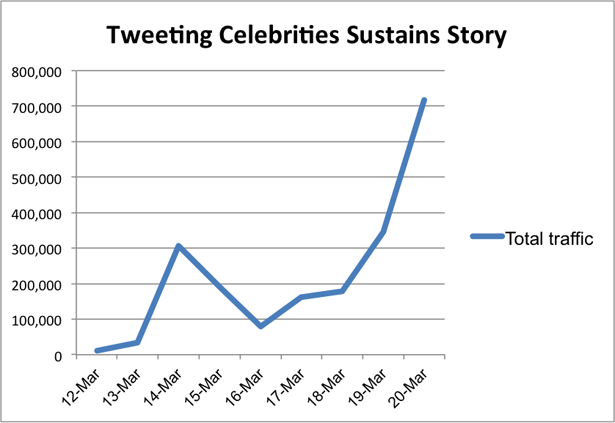

Data released by MIT showed that the internet kept Trayvon's story at the top of the national conversation. Twitter activity exploded shortly after Daniel Maree launched the meme and celebrities helped promote it.

"Around the 17th [attention] starts to dip a bit," said Maree, referring to the chart above. Activity picked up shortly after the hoodie meme began on March 19. "Looking back, that was really scary for me. I was thinking, 'Wow, what if we didn't do this. What if the story had died?'" Even in a democratic country with broad speech opportunities, it can be difficult to gather eyes and ears around an issue and even harder to sustain it in people's minds. The hoodie meme clearly helped keep Trayvon's story going.

Whether it's a dancing cat or a blind activist lawyer, a singing baby or a young man in a hoodie, there's something about internet memes that makes them addictive to watch, pass along and maybe even remix. While the mystery behind Double Rainbow Guy's 35-million-view video will probably remain a mystery, political memes are a little easier to decipher and understand.

Memes wielded for activist ends reflect how a global generation steeped in the idiosyncrasies of Internet culture can bring that culture to bear on serious social issues.

I want to be clear: memes by themselves didn't free Chen Guangcheng from illegal detention, nor will they serve justice in Trayvon Martin's case. And, certainly, as we've seen with examples like Count to Potato and Third World Success, memes have also been used to mock and humiliate other people (including Martin himself). But memes wielded for activist ends reflect how a global generation steeped in the idiosyncrasies of Internet culture can bring that culture to bear on serious social issues.

Take, for instance, the Casually Pepper Spraying Cop meme. Springing up to deliver, in Xeni Jardin's words, "Photoshop justice" for the depicted police brutality, it is a classic example of how internet memes can magnify attention to a cause. The critical difference with the Chen Guangcheng and Trayvon Martin memes is the increased level of organization and intent. They were both deliberately launched by individuals who provided clear instructions for participation. They also developed dedicated web sites to collect images and organize the community.

Even more remarkable is that the sunglasses and hoodies arose independently of each other. They were separated by vastly different cultural, linguistic and political contexts and a difficult to penetrate Great Firewall. But both tapped into deep-seated fears and beliefs. For China's activists, it was the belief that the government would violate rule of law in dealing with human rights activists. In the US, it was the belief that young people of color are frequently profiled as criminals.

Those fears were projected into simple symbols that showed, in Cheese's words, "the personal as political." These symbols--hoodies, sunglasses--served as a sort of grassroots logo, an unforgettable graphic image representative of a larger concern. They're objects almost everyone has and wears, and they're easy to replicate and remix. In contrast to clicking a like button, creating a meme requires a greater commitment in the creative act of posting your own interpretation. Small as that act may be, taking ownership of a meme allows netizens to make themselves a part of the larger message and, in turn, make the message a part of themselves.

It can't be a coincidence that the two groundbreaking activist memes emerged independently from historically disempowered communities eager to have their voices heard. Whether for serious or silly ends, researchers are finding that the participatory creative culture of memes makes for true community building. These bonds can be quite strong for silly cat images; they'd only be more so for issues that touch on deep concerns.

The biggest question is what happens after the meme takes off. Could memes lead to sustained action and real world change? Time will tell, as activists disseminate more memes across the web. The Chen Guangcheng meme demonstrates that they can be effective on their own in lower freedom contexts, where the simple act of speaking out has its own power. But if the flurry around Trayvon Martin is any indication, memes in higher freedom contexts work best in concert with other efforts.

"There's definitely a need to go beyond a click or a share or a photo or a like," Maree said. "It's much more effective to make a long lasting relationship where you can build trust and continual engagement over the lifespan of what you're trying to accomplish. That's going to require, such as in political organizing, inspiring people and giving them value and adding some additional quality to life that enables them to participate on their own terms."

Crazy Crab seems to agree: "I hope that netizens, when clicking the mouse, come closer to actual practice and by sending a picture, they come to support [Chen] Guangcheng. [I want to let] every participant (including those who didn't send a picture) experience this mental process. I hope everyone can think, 'Why do we have fear? What is happening to China? Why? And what should we do?'"

While memes may not always lead to further social and political involvement, we can't easily dismiss or ignore them when they take over our social media feeds. Gathered together, they reveal the power of a united creative community. Whether promoting a censored story or raising awareness of a marginalized one, activist memes show that the addictive, unforgettable power behind LOLCats can also be applied to serious social issues. The peoples, you might say, can haz a voice.