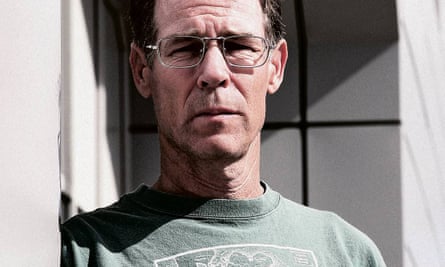

His novels may be shelved alongside dragons from Anne McCaffery and the surreal physics of M John Harrison’s Kefahuchi Tract, but Kim Stanley Robinson insists that he writes science fiction because he’s a realist.

“I think I do science fiction because I feel like if you’re going to write realism about our time, science fiction is simply the best genre to do it in,” Robinson says. “This is because we’re living in a big science fiction novel now that we all co-write together.”

“You write domestic realism and you’ve trapped yourself into a tiny little portion of a much larger reality. You write science fiction and you’re actually writing about the reality that we’re truly in, and that’s what novels ought to do.”

There’s an unavoidable tension between wanting to paint the world as it really is and writing about things that can’t possibly have happened yet – a tension Robinson resolves by limiting himself to the science and technology that we already understand. It’s a strategy that has seen him become one of the leading lights of “hard” science fiction – sci-fi that puts scientific accuracy at its core – as his fictional universe has reached from the near future into the 26th century.

The spacefarers in his latest novel, Aurora, set out on a voyage to a star 11.9 light years away with no warp drives, no sentient robots and no nanomachines. The ship’s technology offers impressive upgrades on familiar 21st-century models, from “printers” that can manufacture anything the travellers require, to a quantum computer so sophisticated it wonders if it should award itself the pronoun “I”. But Robinson’s mission launches in 2545, putting his characters as far away from the world of Taylor Swift and the Apple smartwatch as we are from Niccolò Machiavelli and the matchlock musket. It’s almost as if Thomas More had imagined a captain setting out for the moon in a clipper.

Robinson makes no apology for the 21st-century tech of his 26th-century explorers, arguing that progress in science and technology will asymptotically approach “limits we can’t get past”.

“It’s always wrong to extrapolate by straightforwardly following a curve up,” he explains, “because it tends off towards infinity and physical impossibility. So it’s much better to use the logistic curve, which is basically an S curve.”

Like the adoption of mobile phones, or rabbit populations on an island, things tend to start slowly, work up a head of steam and then reach some kind of saturation point, a natural limit to the system. According to Robinson, science and technology themselves are no exception, making this gradual increase and decrease in the speed of change the “likeliest way to predict the future”.

“We might be in a very steep moment of technological and historical change, but that doesn’t mean that it will stay that steep or even accelerate.” Practical and theoretical constraints, which go beyond even problems such as climate change with which we’re struggling now, will eventually slow us down, Robinson continues. “What I’m assuming is that there are some fundamental issues that are going to keep us from doing things much more spectacularly than we are now.”

For Alastair Reynolds, most of whose space operas are set hundreds if not thousands of years in the future, imagining advanced technology is more a matter of art than science.

“Sitting here at the beginning of the 21st century, we’re only 200 years into the industrial revolution,” Reynolds says. “We don’t have an enormous dataset to draw on, so whatever shaped curve we’re on, we’re only at the beginning of it.”

It’s perfectly conceivable that climate change, theoretical stagnation or social change could see progress level off, Reynolds continues, but linear extrapolation from the past “never really captures the feel of the future”.

“I come at it from a different angle of attack with each novel, searching for the technological texture the story demands. There isn’t a recipe, it’s more of an instinct. Like everyone else, I read newspapers and New Scientist and try to put my finger on the trends which we can just see emerging now that are accelerating and might take off.”

Science fiction authors may find inspiration in cutting-edge research and pre-alpha technology, but it’s dangerous to defend their work as more real than their colleagues working in fantasy or historical fiction.

“You have to be able to invest in your own creations, to suspend your own disbelief in order to be able to write them,” he says. “We all have to draw the line somewhere.”

Ann Leckie, whose Imperial Radch novels are set thousands of years in the future, says the distinction between plausible technology and the kind of hardware that is – in Arthur C Clarke’s memorable phrase – so advanced as to be “indistinguishable from magic” isn’t important for fiction.

“Even in real life I’m not certain the boundary is particularly solid,” she says. “The ‘indistinguishable from magic’ thing is highly dependent on where a viewer is looking from, and not something intrinsic to any particular sort of tech.”

Sometimes Leckie delves into the background of a technology to see what would make it work, and at other times simply tells herself “Yeah, I just want one of the variations on wormholes for interstellar travel, I’ll glue some glitter to mine,” but the starting point is nearly always, “What would make my story work the way I want it to”.

As a novelist, she doesn’t have to justify why some piece of technology is important, or why someone should spend money to develop it, and she doesn’t have to “separate out what’s existing tech from what’s made up”.

“I just put it all together in as artful a form as possible, in a way that will ask interesting questions, or illuminate the issues I’m pondering.” Leckie can hop over any gaps between currently achievable technology and what’s needed for the story and “go on with the adventure. That doesn’t mean I don’t think about that disjunct, of course, just that it’s not something that’s going to trouble me too much once I get going. I only need something to seem like it might mostly fit what we know, I don’t really need to worry too much about the details of how it might happen.”

By definition, Leckie continues, science fiction is concerned with science, but the demand for realism hides a host of assumptions about what’s real and whether fiction can convey objective reality.

“I suspect that we get used to particular sorts of stories being presented in particular sorts of ways, and we’re so used to interpreting them and understanding what it is they’re doing that we think of those forms and styles as faithful, complete depictions of reality. In fact they’re stylised and filtered – they’re just stylised in a way that we’re really, really used to.”

Narrative is such a basic mode of human thought, such a powerful way of organising the world around us that it’s “really easy to think that, looking at the world through a particular narrative frame, we’re looking at the unvarnished truth, the unarguably real. Really, we’re looking at an interpretation of what’s real, labelled and organised by whatever narrative we’ve pulled out of our inventory.”

For Robinson, the narrative frame provided by science fiction gains its power from combining the two disparate elements that give the genre its name.

“‘Science’ implies the world of fact and what we all agree on seems to be true in the natural world. ‘Fiction’ implies values and meanings, the stories we tell to make sense of things.” David Hume argued that it’s impossible to argue from the way the world is to the way the world ought to be, Robinson continues, “and yet here is a genre that claims to be a kind of ‘fact-values’ reconciliation, a bridge between the two”.

“Can it be? Well, no, not really – but it can try.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion